Section 2:

The social care context in the UK and Malaysia

Malaysia:

15% of the population will be aged 60 years and older by 2030.

England:

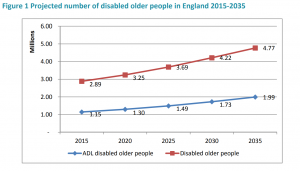

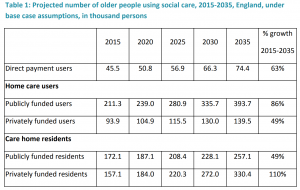

In both countries, longer life expectancy due to better health care and healthier lifestyles (especially for people with disabilities and long-term health conditions) is resulting in a greater demand for social care services.

The impact of the ageing population in the UK and Malaysia

The provision of care for older people relies on both the unpaid care of families and other carers, alongside publicly and privately funded social care services. An ageing population and less reliance on informal care from family members have resulted in an increased demand for social care staff.

The Size and Structure of the Adult Social Care Sector and Workforce in England 2014 report estimates that the number of paid adult social care jobs in 2025 could increase from 1.52 million to between 1.82 and 2.34 million – an increase of between 20% and 54% in a relatively short time period. The sector needs new workers to keep up with the increasing demand. But also, there are issues such as high vacancy rates and poor staff retention. This stretches the numbers of workers required to keep up with demand, even further.

How is the care sector in the UK managed?

Social care in England, Scotland and Wales is split into regions known as local authorities (England and Wales) or unitary authorities (Scotland).

32 in Scotland | 22 in Wales

As of July 2022, 42 Integrated Care Systems have been established in England to plan and deliver health and care services. These have been created to produce more ‘joined up’ approaches to ensuring the health and well-being of local populations.

They feature Integrated Care Partnerships which include not only health care professionals, but also community organisations, local authorities, patient groups and others representing local communities. In Northern Ireland, seventeen Integrated Care Partnerships have played a similar role in developing strategies for delivering health and social care since 2013.

What do social care workers do?

Of the adult social care workforce in England:

How social care is delivered in the UK

Social care is provided separately to health care in England, Scotland and Wales. In some instances, funding for health and social care may be pooled to buy integrated health and social care services for adults.

In Northern Ireland, health and social care are integrated, where services are commissioned and provided through five trusts.

Social care offered to adults in England on the basis of whether or not a person’s needs are assessed to be severe enough to receive care. Local authorities use national criteria to assess individual needs

Briefly, the criteria are based on whether or not an individual can achieve certain outcomes in daily life. And, if they can’t, whether or not there is an impact on their well-being.

Individuals are only eligible for care if they have very high needs – that is, they have a lot of difficulty with at least two of the outcomes listed. Many will not be considered eligible for care [2]. If an individual isn’t eligible for care under the national criteria, they can arrange and pay for their own care through private providers.

[LINK TO MORE INFO]

Read the Age Concern’s eligibility criteria for social care across the UK.

Read about Adult Social Care in the UK

2016

• 1,811,000 new requests for support

• 57% resulted in no ‘direct’ support from the council

How is the care sector in Malaysia managed?

In Malaysia the social care sector is mainly managed and provided by the government, and organised by the Department of Social Welfare Malaysia (DSWM) under the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development. Facilities and services are also provided by non-governmental, charitable and religious organisations.

There are three categories of residential care:

• Public residential homes – directly under DSWM under the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development

• Private residential homes – managed by voluntary organization and private agencies which are profits driven

• Religious homes – privately owned and mainly derived from religious pursuit.

[IN NUMBERS GRAPHIC]

• RM 6 billion spent on the elderly in 2015, which is expected to increase to RM 33 billion in 2030.

• 10 residential homes for independent elderly, Rumah Seri Kenangan (RSK)

• 2 public nursing homes for critically ill or bedridden elderly, known as Rumah Ehsan (RE)

Non-residential care in Malaysia

Daily activity centres

Department of Social Welfare funds a non-residential type of social care known as the daily activity centre (Pusat Aktiviti Warga Emas, PAWE). The daily activity centres are run by elderly representatives of the community.

Home help

Home help services are directly supervised by DSWM. Home help services are volunteer-run, providing domiciliary social care for older people.

Current trends in Malaysian social care

[VIDEO: With MyAgeing]

Trend 1. A move towards ‘ageing in place’

Demands are increasing on social care services in Malaysia. Independent or semi-dependent older persons are encouraged to stay in their own homes, with support from social care workers limited minimal assistance in conducting daily activities in their own place.

One of the managers of a care home that we spoke to emphasised the role of the centre for “rehabilitation and neutralisation” – and the value of continuing normal life in the community once they have recovered sufficiently. This kind of domiciliary care has been widely and aggressively implemented in many developed countries, including England.

Discover more about the ageing in place initiative promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO)

Trend 2. A move away from a voluntary approach

The voluntary approach that was adopted by the Department of Social Welfare Malaysia to implement the Home Help Program should be revised and switched to a more effective strategy.

Older persons who are fully dependent with no family members are better served and managed in the institutional care that integrates both medical and social care services.

As the majority of older people in Malaysia are considerably cash poor, the government should also find an alternative future pathway. Possible routes include long term care insurance. This would increase the accessibility and affordability of care services for those in need.

REFERENCES

1. Ham, C., et al., Integrated care in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. 2013, King’s Fund: London.

2. Reade, N (2015). The Surprising Truth About Older Workers. AARP The Magazine. Available at https://www.aarp.org/work/job-hunting/info-07-2013/older-workers-more-valuable.html

3. Reynolds, F. A., Farrow, A., Blank, A. (2012). ‘Otherwise it would be nothing but cruises’: Exploring the subjective benefits of working beyond 65. IJAL. 7(1):79–106. doi: 10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.127179.

4. Sewdas, R., de Wind, A., van der Zwaan, L. G., van der Borg, W. E., Steenbeek, R., van der Beek, A. J., & Boot, C. R. (2017). Why older workers work beyond the retirement age: a qualitative study. BMC public health, 17(1), 672.

Course navigation